SOUTHERN MOUNTAINS TRIAL (1960) by Dave Johnson Oct 2016

The 1960 Southern Mountains Trial was run by the Australian Sporting Car Club to promote a longer event around NSW, following the demise of the annual Round Australia Ampol and Mobilgas Trials.

The ASCC had started the Redex and Ampol Trials, and were already running 500 mile (800 kilometre) weekend events in NSW. ASCC then conceived the idea of using the June long weekend to run a longer event.

It wasn’t that the 800 km events of the Antill Trophy Trial and the Mac Hicks Trial weren’t testing enough. With the poor maps and even poorer roads of the day, not to mention the limitations of car design in those days, those trials were already testing cars and crews pretty well.

Planned at 1,500 miles (2400 km), the Southern Mountains Trial would be the longest event run in such a short time, and would remind crews from the 800 km events what the ‘tyranny of distance’ really meant. Over the 3-day long weekend, the Trial was planned to run from Sydney to the Victorian border, in the vicinity of Eden, and back again .

The Trial

The only report available of the event is one written by the Director, Desmond Pinn, in the July 1960 edition of Sports Car World. The scanned copy of the article is poor. Consequently the following details have been extracted and supplemented by this writer’s recollections of the part of the event that he completed. The essentials are that 15 competitors started the Trial, of whom only 4 finished, even after the Trial had been shortened

The course

The Southern Mountains Trial left Sydney (ASCC Clubrooms in Redfern) at 3 minute intervals from 2pm Saturday. From there the course went to Lithgow where the serious stuff started. In those days the run over the Blue Mountains was not the speed limited nightmare it is today but I cannot remember whether we went by Bells Line of Road or via Springwood.

Then off to Tarana, Sodwalls, O’Connell, Wisemans Creek, Essington, Campbells River Crossing, Rockley, Trunkey, Abercrombie Mountains, Tuena, Markdale, Bigga, Reids Flat, Rugby, Rye Park and Worgela to Yass. Some of these roads have been little used since the time of the first Southern Mountains but have a look on a map and see where these localities and towns are.

At Yass the placings were: Murray 11 points, Sly 14 pts, Moore 17 pts, Kennedy 30 pts, McKay 31 pts, and Burns 45 pts. Note that one point represents one minute lateness, in an event timed to the minute.

From Yass the course travelled via Nerriga (no mention or recollection of which road we used from Yass to Nerriga), Nelligen, Runnyford, Mogo, Moruya, Araluen, then to Braidwood, arriving at 4.15 am Sunday. (The Nerriga road has had two complete realignments since then. The Moruya to Araluen road has been listed as one of Australia’s best rally roads.)

The course then took competitors to Cooma, down the Brown Mountain to Bemboka, then to Candelo for breakfast and a one-hour break.

At this point the placings were Murray first with Moore closing the gap in second place and McKay in third.

From Candelo the course looped via Mt Tantawangelo, Bombala, Rockton, Pericoe, Wyndham, back to Candelo for tea and a 10-hour break. Departing Candelo at 1.45 am Monday, competitors travelled via Mt Tantawangelo to Cooma, Tharwa, the Cotter Dam, Uriarra back to Yass.

At Yass the event was concluded by mutual consent of the few remaining competitors and the Director as the gaps between cars seemed unlikely to close and only misfortune would have changed the placings.

The Results

From the 15 starters, the results were:

First Place : Leigh Moore and Pat Lawless (Holden) 44 points

Second Place: David McKay and John McKittrick (Fiat 1800) 87 points

Third Place: Bill Burns and Bede McNabb (Jaguar) 147 points

The casualties

The Director likened the drop out of cars to the 10 little nigger boys, so this counting has been included from the article in deference to his words. Fortunately the Trial was terminated before the numbering got close to “then there were none”.

Jack Thornton (Vanguard) brakes failed before O’Connell. Then there were 14.

Newton (Ford Customline) damaged car in dry rock strewn creek bed at Tuena control at the bottom of the mountains. Murray was following and avoided the creek bed. Then there were 13.

Higgins (Fiat 1000) became inverted on the road into Yass. Now 12.

Smythe and Kevan Houley (MG) holed sump after Nerriga. Now 11.

Carl Kennedy (Peugeot) front shockers, gearbox and fuel shortage. Out before Nelligen. Now 10.

Ken Burge (Holden) electrical failure before Nelligen. Now 9.

Krantacke (Morris Minor 1000) and Coulson (Hillman) retired due to lateness at Braidwood. Down to 7.

Leon Sly (Ford Zephyr) retired with fuel problems after first climb of Mt Tantawangelo. Now there were 6.

Jack Murray and Dave Johnson (Simca Aronde). Hit fallen tree near Rockton while in the lead. Now 5

According to the Director’s article in Sports Car World we were now down to 4 cars., However the count is actually 5, so I think that an earlier reference to a Lloyd TS without reference to a driver, being in trouble may have spelt its retirement

Also we don’t have any mention of the fourth-placed car as we have accounted for everyone that the article mentions. So a mystery remains as the words from the Director are:

“The remaining 4 cars reached Candelo for tea but all lost points. Moore lost 8, McKay 11 and Burns 13. Ten hours rest followed at Candelo. The three remaining, refreshed crews left Candelo at 1.45am Monday for the return ascent of Mt Tantawangelo, this time in the dark.”

Reflections

My assessment of the distance that they actually travelled before they called it off is close to 1000miles (1600kms) and that is the distance that was repeated for several years before it became the Snowy Mountains Rally, the Snowy Rally and then, in 1973, the Bega Valley Rally.

The dominance by Moore and Lawless from Canberra of the NSW Championships for the first couple of years was a preview of what was to come out of the ACT in years to come.

Although best known for his performances on the track David McKay was a very strong competitor in trials in those days, as is evidenced by his regular participation in the Round Australia events. His navigator John McKittrick was a prominent Sydney Surveyor.

During this period there was little differentiation between the forms of motorsport. David McKay, Jack Murray and Bill Burns would appear regularly in the results of a trial one weekend, a hillclimb the next and a track event on the next. Both Jack and David competed at Bathurst at various times.

We were emerging from the era where motorsport was every form of use of a car competing with someone else and there was little of the specialisation we were to see in the sport in the future.

Bill Burns was a Sydney taxi driver and well known for his beloved Jaguar.

His navigator, Bede McNabb, a butcher, eventually moving to Goulburn, was with me on the first Trials Co-ordination Panel for NSW in 1958, later renamed the NSW Rally Panel.

Putting car trials of the ‘50s and ‘60s in perspective

( Primary contributors. Section on cars by Barry Ferguson and Bob Moore. Maps, Roads and Technology by Dave Johnson, I have endeavoured to remove the first person from my writing but please accept my apologies for any examples still remaining. DJ)

Conditions for trials / rallies in the ‘50s and ‘60s were a different from what we know today (2017).

We have tried to paint a picture of these conditions looking at Roads , Cars and Maps.

Most major roads in NSW are now sealed in bitumen, with at least one lane in each direction, and with marked centre-lines and, possibly, lines along the sides. Warning signs are often in place for dangerous bends. Many secondary roads are sealed, often with centre-lines and warning signs. Highways are well aligned, multi-laned constructions.

Roads in in the ‘50s and ‘60s

Although NSW had some trials before 1953, it was the year of the first of the Round Australia Trials and notable in the history of Australian / NSW rallying and an appropriate date to comment on.

This was only 8 years after the end of World War II, and there was not money around at any level of government to spend on infrastructure, particularly in the country. Maintenance of roads was all that could be achieved. Consequently the road formation and the alignments were basically what had been built in the 30’s, before the Depression that stopped all growth for several years.

Road construction before the war had little in the way of heavy machinery. Typically construction gangs went around hills and mountains, and often made the roads little wider than one and a half cars with spaces for passing.

Bitumen was a fairly scarce commodity. The main highways were sealed in the 60s. I recall, when driving down from Sydney to the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, that there were still some sections of the Hume Highway that were still gravel. On that trip many cars were bogged after the rain on the Highway.

Most secondary roads were still gravel in the ‘60s. Advisory speed signs had yet to be thought of. Warning signs were installed only where there was real danger, not the ‘nanny state’ concept of today.

One of the problems of the ‘50s was that the roads that trials competitors wanted to use were normally reasonable construction only up to the last farmer’s gate. After that they were not regularly maintained by the shire, and their condition became poor. Sometimes finding an old road meant finding one that only the bullock teams had previously used. Also there was the real problem that the farmer actually considered the road into his property from the main road was “his” road, and that meant that using those roads sometimes led to another form of hazard as well.

There was not the demand for the road network anyway, as the number of cars on the road in those days was minute compared with today. Early attempts to get some numbers of cars that were registered in 1950. 1960 and today from the internet have not been successful but that would assist the story. My guess about 10%. Give or take.

Then and now

Look at those parts of the old Hume Highway where it is visible and remember that what you are looking at were the good roads. Those parts that are still used have been maintained but still retain the barely 2 lanes but at least sealed.

The road south out of Thirlmere to Hilltop and Colo Vale was gravel for most of the 60s. It only had good alignments because it had been built on the old railway line that provided a crossing of the very deep Ropesend Creek.

The long and challenging road from Oberon to Goulburn across the Abercrombie Gorge remained unsealed to the end of the 20th century.

The Nerriga road from Braidwood to Nowra was used many times in the ‘50s and ‘60s. We were held up for 2 ½ hours in one event when Tianjara Creek flooded, blocking us on this road when in the lead, and almost carrying us downstream when we stuck the nose of the car into it. The rest of the field arrived just before we tried again to cross, this time successfully.

It was shortly after Tianjara Creek that Lucien Bianchi had the ill-fated crash with the Mini in the closing stages of the 1968 London to Sydney marathon, costing Bianchi the win In 1968 the road was gravel/dirt with poor alignments and lots of bends. When we re-visited the Marathon course in the early 2000s we used a later alignment (still unsealed but with all the tight bends straightened out) but we could still see all of the old road and we were able to find the Bianchi accident site.

The current ‘new bitumen road’ (Nowra to Nerriga) was under construction in 2008, ignoring all the old alignments and streamlining the complete alignment.

Cars in the ‘50s and ‘60s by Barry Ferguson and Bob Moore

In the main the cars “trialled / rallied” were stock standard cars with only minor modifications. They were driven to, in and from the events and service vehicles were a very rare thing.

The majority of cars were sold with drum brakes all round, generators that provided only a fraction of the power of alternators, and headlights with incandescent bulbs – quartz-halogen bulbs had yet to be invented.

Driving lights were very poor by standards of today with their performance falling far short of a quartz-halogen driving light, let alone a light fitted with HID or LED.

To add to the challenge, cars were still using cross-ply tyres, with none of the grip or sidewall strength of modern-day rally tyres.

A lap / sash seat belt was a fitting that we installed ourselves to stop us bouncing around in the cars on the rough roads.

A VW beetle of the 50s and 60s had only a six volt system and the use of 2 driving lights generally resulted in a flat battery by about 2 am. Consequently it was not feasible to use more than two driving lights,

Sump guards and petrol tank shields used were of a very primitive nature.

Believe it or not some cars did not have trip meters and many cars ran a speedo (with a trip) from another model car. Many a driver had to watch the odometer while driving because it was still in front of him and not over with the navigator.

It is hard to imagine today that the now classic cars identified today, were the ones used in trials in the past.

To name some of the popular : Vanguard, Hillman, Humber, Ford Zephyr, VW, Peugeot 203 and 403, Skoda, MG, Chrysler, early Ford V8 were all seen in the events. Look at the makes of cars in the early Round Australias to get an idea of the range of vehicles used.

As we all now know the arrival of the Peugeot 203 and 403 and then the VW beetle set new standards for performance on rough roads and a new level of reliability.

Vehicle modifications of substance did not happen till the early 60s with the likes of performance Holden heads from Waggot Engineering in Sydney.

Maps of the ‘50s by Dave Johnson

In qualifying the maps available to us for rallying or trials as we knew them then I was very experienced in the field. I was training as a surveyor in my first years in the sport, had been using 1” to 1 mile Army maps in Scouts since the age of 15. Since then I have served in the Army Topographical mapping branch and am a member of ANZ Map Society.

As far as maps were concerned, there was nothing available in the ‘50s at all like we have today.

There were some 1” to the mile (1:63,360) maps available for parts of NSW. Sydney was covered, and went as far as Katoomba, Picton and the Hawkesbury River. The rural centres of Wagga, Albury and Tamworth all had 1 or 2 maps cover the town area. Newcastle and Wollongong had slightly wider coverage.

As part of its response to hostilities in World War II, the Army had produced emergency editions of a 4 mile to the inch (1:253 440,) series of the whole of Australia, but the information on them was basic. They had the latitude and longitude co-ordinates of all airports and many airfields, observatories and some prominent objects. The rest of any detail was inserted as schematic only.

They showed that a road went between these two towns with as much compiled information as was available. Very basic.!!!

While aerial photography had been used towards the end of the war, it had not been developed past that stage due to the limitations on finance. The first of a real 1:250k map were produced in the late 50s and continued into the 60s and they are what we use today in the “historic style” of navigation as they were still in Imperial scales using yards.

So what maps were available? The oil companies had made some maps of the NSW and that was the base. The Lands Department had produced “Tourist Maps” of NSW. The Lands Department had access to all boundary survey maps (cadastral) and incorporated much of this into those maps .

The most prolific and sought-after maps of the day were from the NRMA.

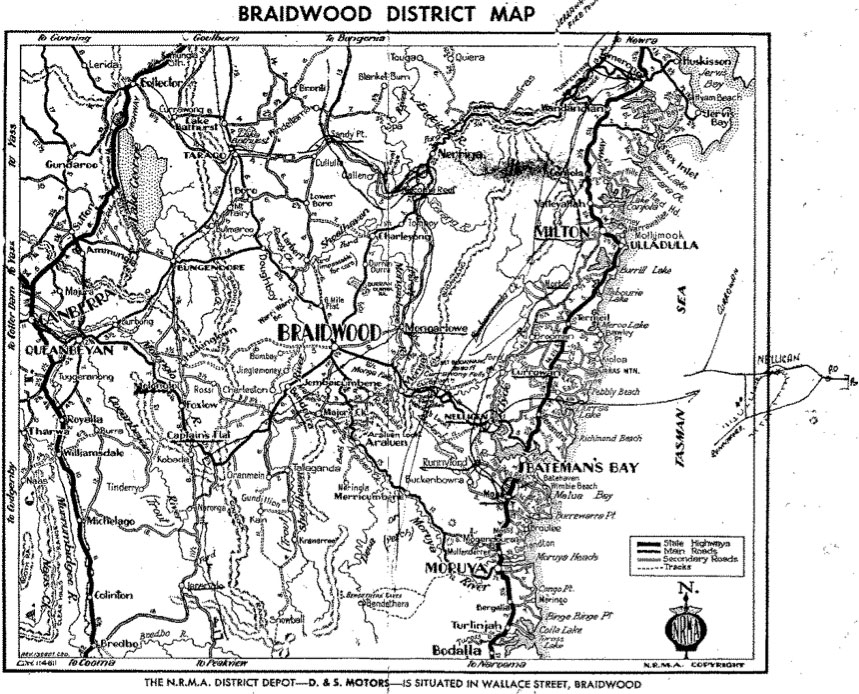

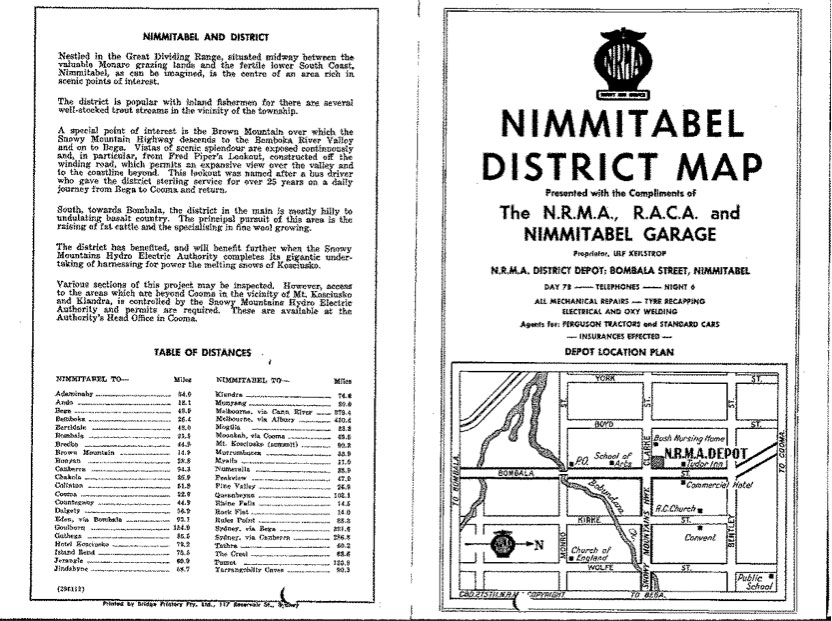

The NRMA produced a multitude of maps in numerous series over the years, starting with what was called the NRMA District Maps. They were produced for the various NRMA district depots in towns across NSW. The oldest that I still have is from 1946 and they run through until 1963 in that form.

They were a quarto-sized ( 214mm x 282mm ) map printed on both sides. These maps showed the town detail with for the location of the NRMA depot on one side, and the surrounding district on the other.

These maps were highly sought-after. Their existence was kept a secret from even your best friend in the next car, if possible, because they were a competitive advantage. Just like the maps in past eras, these maps gave you knowledge that was hard to obtain.

Unfortunately the maps sometimes showed conflicting information and so it then came to interpretation to work out what was really right on the road.

So until the ‘new army maps of the 50s and 60s came into a full coverage these NRMA maps and whatever else we could come up although scarce and sometimes very basic, were the best we could find to use.

Here is one of the earliest that I have together with a sample of the front of another.

Remember they are scaled in miles.

It appears that the end of the hard copy maps from the NRMA is at hand with news that the current stocks of the large NRMA maps are the last to be delivered to branches in NSW.

The Braidwood District map has another story attached to it.

Do we need to add a section on technology?

What did competitors use for compasses and tripmeters

Initially there was nothing in the way of special distance measuring devices. I remember people taking the tripmeters out of old cars and jigging them to work as a separate dial in the car, with the winder to turn them back to zero. Then we extended cables and got them over in front of the navigator.

Slowly we got hold of Haldas, mainly through Race and Rally which was founded in the 60s by Peter Mulder and started to cater for motorsport needs.

The Halda had two gears that you would change according to a special chart after calculating the needed correction to have the odometer agree with the event organisers.

The varieties used in rallies has not really changed between 1953 and 2013 when we started to access the GPS signal to give us the bearing of the direction of travel.

The other really significant issue was timing.

In the 50s and 60s clocks suitable for rally purposes just weren’t manufactured. The procedure that became the norm for a long time was the ‘selaed watch’ system.

A cigarette tin which was common in the day, about 8 cms square and 2 cms thick would have a circular hole cut in the lid about 4 or 5 cms in diameter and a piece of Perspex cut to fit inside the tin.

Your watch is then placed in the tin and sealed with wire and lead seals. The competitor would carry with them and present to the control officials along the course. There are heaps of stories about the things that the navigators of the day got up to in an effort gain advantages with these tins.

These are some of the issues relative to Trials in the 50s.

Barry, Bob and Dave March 2017